How to shape the new Crisis and Resilience Fund

The government’s announcement of the new Crisis and Resilience Fund (CRF) represents a major shift in how England supports people facing sudden financial hardship. For the first time in over a decade, councils will receive multi year, ring fenced funding to run discretionary crisis support.

This policy comprises £1 billion per year for three years, beginning April 2026, with £842 million allocated to English local authorities. This long term settlement replaces the short, six month funding cycles of the Household Support Fund (HSF) that councils have had to navigate since 2021.

Importantly, the CRF is explicitly linked to the government’s commitment to end the need for emergency food parcels. This signals a shift away from short term fixes towards a system focused on prevention, dignity and financial resilience.

But for the CRF to fulfil this ambition, it must learn from the evidence: who is in crisis, why, how councils have been delivering support under the HSF, and which models work best to prevent hardship.

This blog summarises key findings from Resetting local crisis support in England: Recommendations for the new Crisis and Resilience Fund, jointly authored by Trussell and Policy in Practice.

Join our free webinar on shaping the Crisis Resilience Fund

Register to hear Trussell and Policy in Practice discuss this analysis and recommendations in our free webinar. Of particular interest to councils, as well as organisations supporting people at risk of financial hardship

Why the CRF matters

Financial insecurity remains widespread across England. About one in ten low-income households (9.2%) were in negative budgets in June 2025, with an average shortfall of around £400 per month.

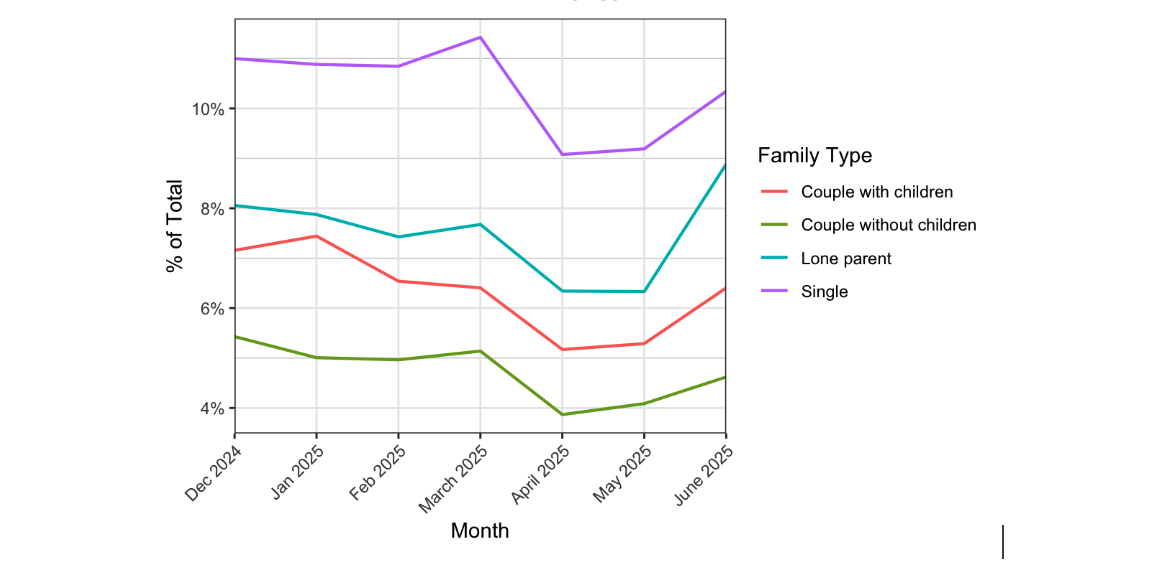

Some groups face particularly deep or persistent financial strain. Working-age households are most likely to be in negative budgets. Different household types experience different levels and depths of financial pressure: families with children are less likely to fall into crisis, but when they do, they face deeper shortfalls (for example, lone parents average £465 per month in deficits).

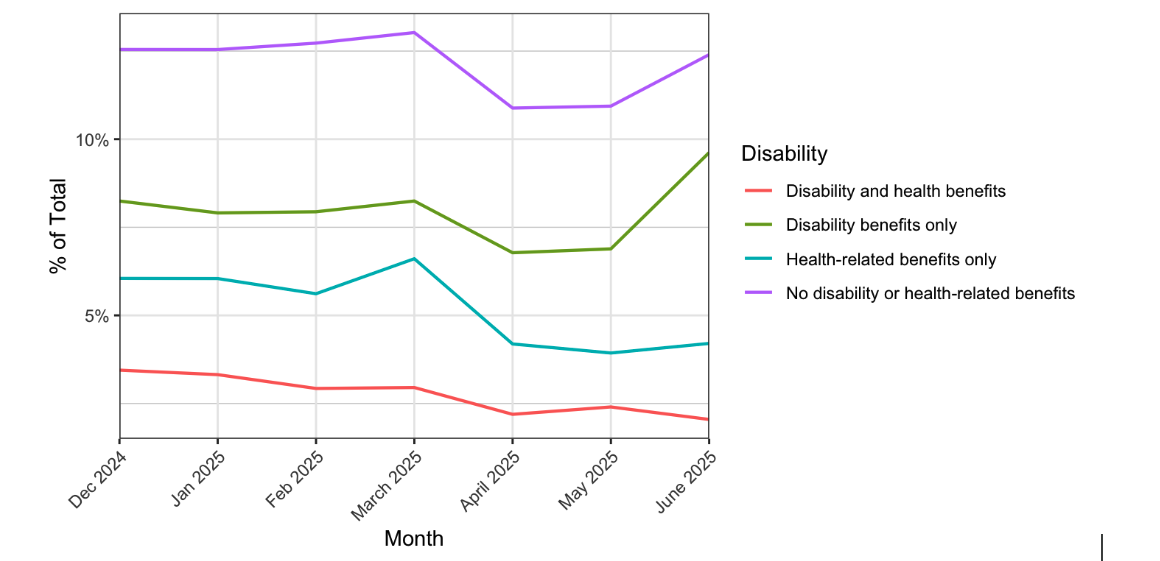

Similarly, when focusing on disability status, disability benefits reduce the likelihood of negative budgets, but when shortfalls occur, they tend to be larger for households with disabilities.

Figure 1. Percentage of low income families with a negative budget after expected essential costs, by disability or health related benefit

Source: Policy in Practice analysis of benefit administration records from 36 English local authorities in the Low Income Family Tracker (LIFT), December 2024 to June 2025

Our analysis also considered wider structural pressures, including the freeze in Local Housing Allowance (LHA) and rising private rents. Both directly affect how much families must spend on essential costs. As rent takes up a growing share of household budgets, more families are likely to fall into negative budgets, increasing the demand for crisis support.

The CRF cannot replace the need for an adequate social security system. However, it can help ensure that when households do experience a financial shock, the support they receive is dignified, effective, and focused on preventing hardship from escalating.

Pressures, patterns and promising models

Household financial pressures

Negative budgets are rising again after a brief dip, and certain groups consistently face deeper cash shortfalls. For families with children, especially lone parents, a single unexpected cost can push the household into crisis.

Figure 2. Percentage of low income families with a negative budget after expected essential costs, by family type

Source: Policy in Practice analysis of benefit administration records from 36 English local authorities in the Low Income Family Tracker (LIFT), December 2024 to June 2025

These findings reinforce the central principle of the report: crisis support should be cash-first. Households need flexibility to meet real emergencies, whether that is rent, food, utilities or essential items.

Current delivery approaches under the Household Support Fund (HSF)

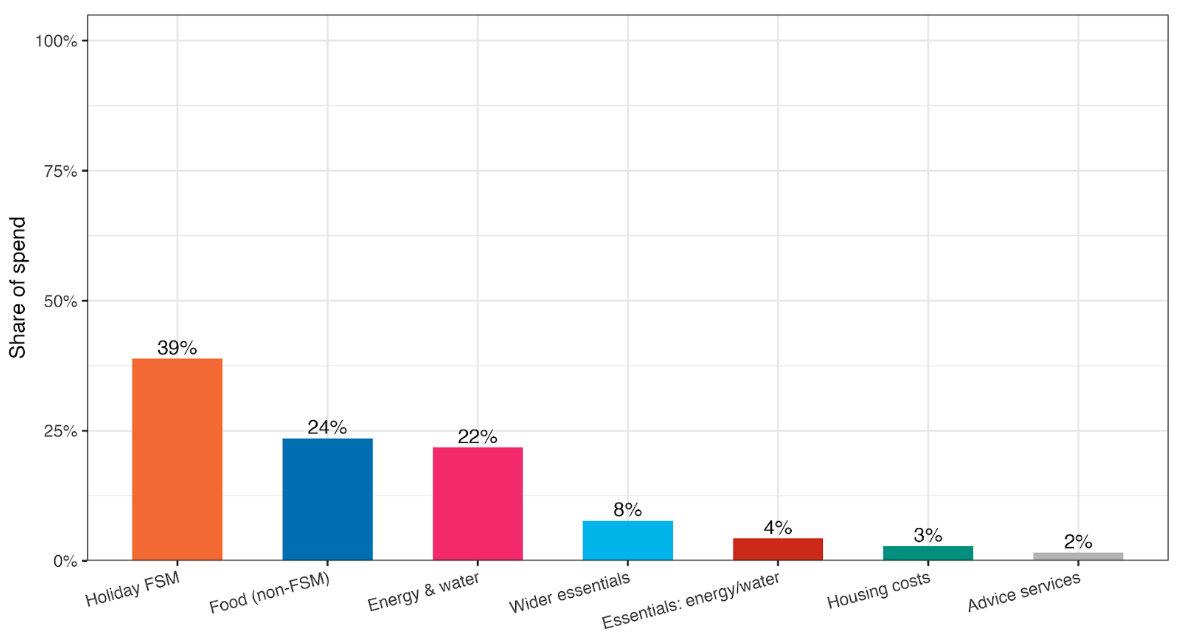

HSF data shows that 65% of spending on average goes to families with children. The largest spending categories are holiday FSM support (39%), food (non-FSM) (24%), energy/water (22%).

Figure 3. National average spend by expense type

Note: Percentages are average reported shares; categories may overlap, so bars do not sum to 100%. Source: Policy in Practice analysis based on HSF4 management information

Short-term funding and guidance shaped these patterns, often encouraging voucher-led models, particularly during school holidays.

However, there are strong examples of good practice: some councils provide fast, cash-first crisis grants, while others integrate cash support, advice and warm referrals, offering more holistic responses to financial crisis. The diverse practices are evidenced in the three delivery patterns we identified in our cluster analysis.

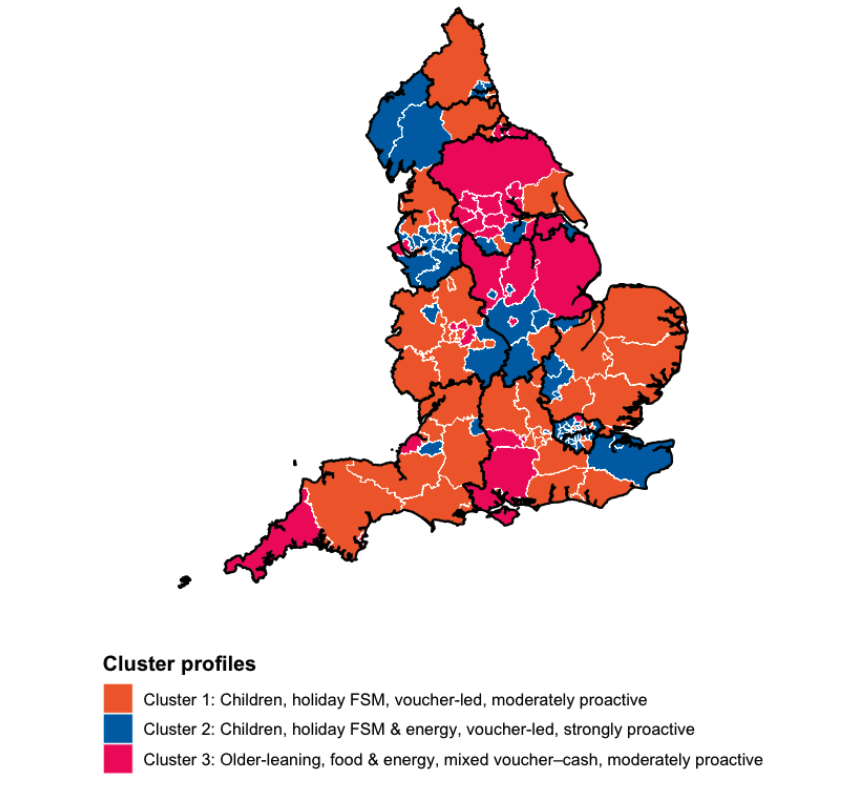

Figure 4. Profiles of HSF spend by Unitary Authority

Source: Policy in Practice analysis based on HSF4 management information

- Cluster 1: Children-FSM, voucher-led, moderately proactive: This group of local authorities directs a large share of funding towards holiday FSM and other holiday food provision for families with children. Support is mainly delivered through vouchers, with a moderate level of proactive outreach alongside application-based support

- Cluster 2: Children-FSM + energy, voucher-led, strongly proactive: Councils in this group follow a similar voucher-based model but combine it with strong proactive delivery, reaching out directly to eligible families and allocating a slightly higher share to energy support

- Cluster 3: Older-leaning, food and energy, mixed voucher–cash, moderately proactive: This cluster focuses more on supporting older households, with higher spending on energy and food costs, and uses a more mixed approach combining vouchers and cash awards

This spatial variation highlights how local context and institutional practice play a major role in shaping delivery approaches. It also reinforces the importance of improving the consistency of support under the CRF, while allowing some flexibility to meet the specific needs of local populations.

Evidence from the frontline

Trussell’s data and insights from frontline food aid providers show that people who turn to food banks are experiencing income crises, not difficulties accessing food itself. The report emphasises that being unable to afford food is a symptom of wider financial strain, driven by pressures such as rent, utilities, clothing and other essentials becoming unaffordable.

Because the root problem is lack of income, free or low cost food alone cannot prevent crises or build resilience. Cash support is more effective and more dignified than vouchers, and local schemes work best when they are connected to advice and support services that help address underlying issues.

A key part of this is warm referral pathways. Rather than simply signposting someone to another service, warm referrals involve actively connecting people to support, for example by introducing them directly to an adviser or helping them take the next step. This approach makes it more likely that people receive the help they need, reduces repeat crises and strengthens trust in local support systems.

Together, these insights reinforce the report’s message that the CRF should focus on resilience, prevention and income-based solutions, not food provision.

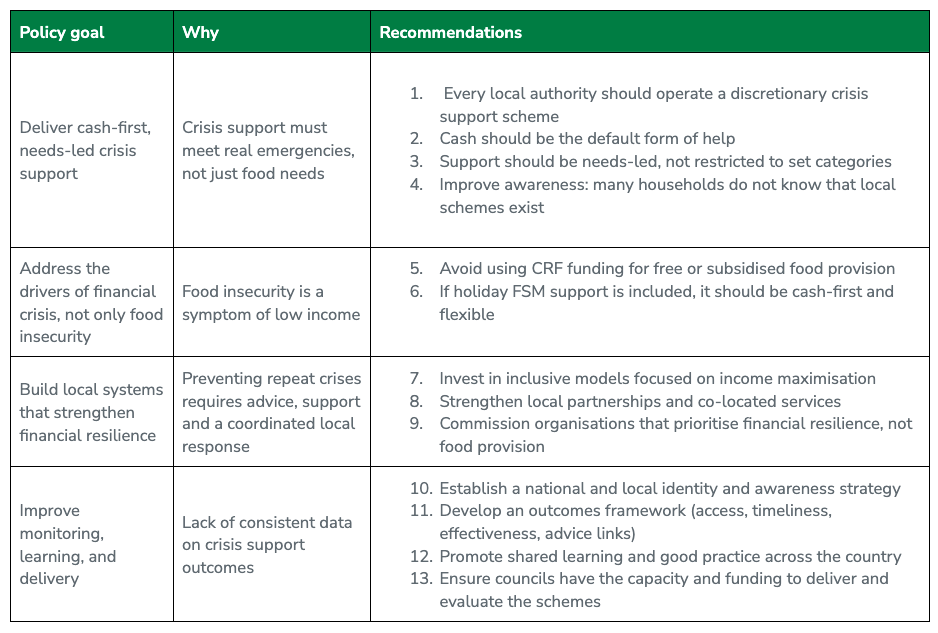

What we recommend for the development of CRF

The CRF is a unique opportunity to redesign crisis support in England so that it is fair, effective and preventative. It gives councils the stability to plan ahead, strengthen partnerships and create crisis support systems that help residents before hardship deepens.

But the success of the CRF will depend on three things:

- Using data for good: Understanding who is in crisis and why

- Scaling existing good practice: cash-first models, warm referrals, advice integration and effective targeting

- Building a system focused on income, not food

If implemented well, the CRF can reduce the need for emergency food parcels and help people move toward greater financial security, fulfilling the government’s ambition and the goals of councils, community organisations, and residents across England.

The table below summarises our recommendations.

Recommendations for the development of the Crisis Resilience Fund

Analysis, recommendations… What about practice?

Policy in Practice has previously been shortlisted for an LGC Award recognising our work with nine councils that helped allocate £18.5 million in Household Support Fund support, reaching 149,000 households and awarding an average of £100 to £200 each.

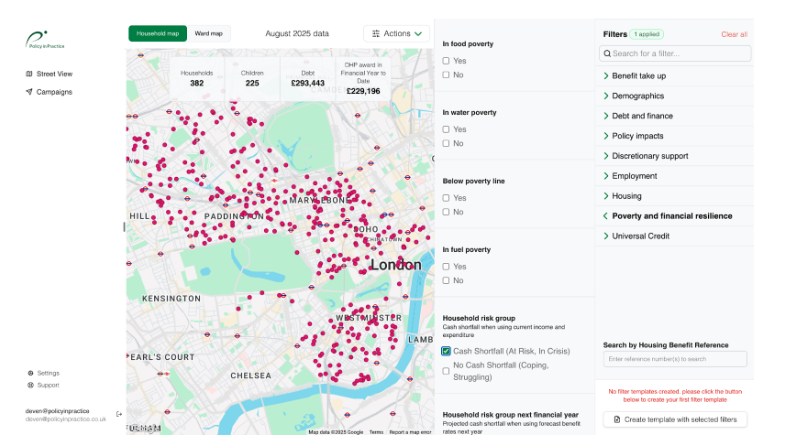

Councils used our Low Income Family Tracker (LIFT) platform to identify families most in need, combining proactive outreach with short-term financial support and longer-term plans to reduce the risk of households falling into crisis again.

Our latest report highlights six good practice examples, including two that show how councils have used our Better Off Calculator and LIFT platform to deliver effective, targeted support.

“The new Crisis and Resilience Fund brings welcome stability, but councils will need to deliver a new scheme at speed. We are helping authorities implement the fund through our policy expertise, experience and practical data driven capabilities. In this report we share best practice gathered from helping over 100 local authorities proactively target support accurately and efficiently."

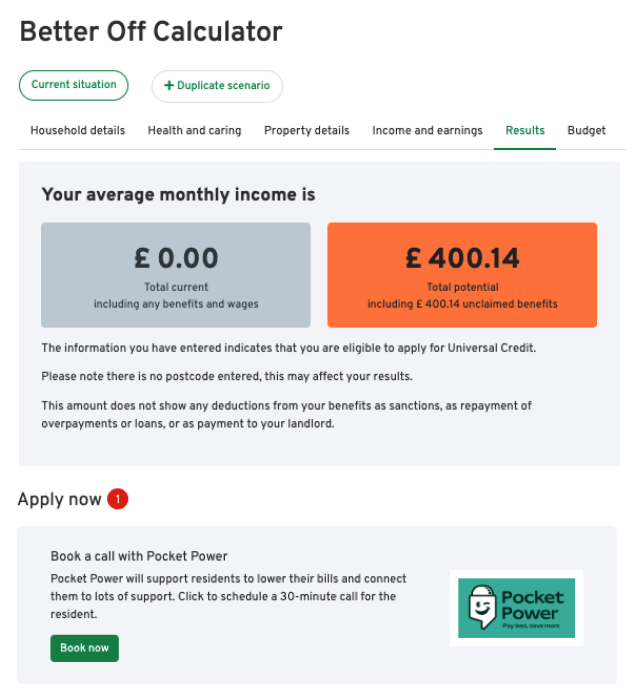

Good practice example 1: Policy in Practice and Pocket Power: Better Off Calculator integration

To help social housing providers support residents facing financial hardship, Policy in Practice partnered with Pocket Power to connect income maximisation with cost of living support. The goal was to help residents access help more swiftly, strengthen their financial wellbeing, and enable providers to better manage rent arrears.

The partnership involved a software integration linking Policy in Practice’s Better Off Calculator (BOC) directly with Pocket Power’s phone-based savings service. This enables housing advisors to make a warm referral directly from the BOC platform, creating a single, seamless pathway for residents to both identify unclaimed benefits and reduce their everyday costs.

A key feature of the integration is that, with residents’ consent, data entered into the BOC is securely pre-populated into Pocket Power’s system. This avoids the need for residents to repeat their information, saving time and reducing stress. The phone-based model is particularly valuable for people who are digitally excluded or lack confidence using online tools, helping ensure that savings opportunities are accessible to everyone.

The project has shown strong results. To date, Pocket Power has helped 6,000 people save a total of £1.5 million, an average of £250 per person. Among users, 88% report feeling less stressed about their finances and 90% feel more able to manage their bills. The benefits are illustrated by the case of Matthew, a resident referred via the BOC who saved £540 per year after a single call, describing the process as “simple and quick.”

This model offers a practical, person-centred approach to supporting households in financial distress. By increasing disposable income through both income maximisation and cost of living support, it helps reduce the immediate pressures of financial crisis while building a more stable foundation for long term resilience.

Sample sections of the Better Off Calculator (BOC), a tool used by individuals and support organisations to check benefit eligibility and connect to wider financial support

Good practice example 2: South Norfolk and Broadland: Preventing financial crises through early intervention

South Norfolk and Broadland councils had discretionary funds to support families facing financial crisis. Without data led targeting, support risked being reactive, reaching households only once problems had escalated.

The councils used their data via our LIFT platform to proactively identify households in arrears and at high risk of financial crisis, focusing on those with low repayment capacity. Officers engaged residents early to provide tailored financial support and income maximisation advice, ensuring cash help reached those who needed it most.

As a result, the councils recovered £11,000 in arrears across 9 households, alongside the provision of targeted financial assistance. This helped prevent further crises for families in vulnerable situations and ensured discretionary funds were deployed strategically, avoiding higher downstream costs.

This is a clear example of how councils can use existing data to target discretionary support, using a cash-first approach to help households at high risk of financial crisis avoid severe financial hardship and build longer term financial resilience.

Sample view of the Low Income Family Tracker (LIFT), the analytics tool councils use to target support to households

How we carried out the analysis

This blog draws on the same evidence used in the full report: a combination of large-scale administrative data, national monitoring data, and insights from organisations working directly with people in hardship.

Household-level data from 36 local authorities

Our analysis covered 36 local authorities and millions of household-month records from benefit administration data between December 2024 and June 2025. These records include households receiving Council Tax Support, Housing Benefit, and, in some areas, Universal Credit. They represent people living on the lowest incomes who are at higher risk of experiencing a financial crisis.

By comparing household income with estimated essential costs (using ONS Family Spending data uprated for inflation), we identified households in negative budgets, meaning their income was not enough to cover even the basics. This helps us understand which groups are most vulnerable and where the CRF will need to focus.

Household Support Fund monitoring data (HSF4)

We also analysed national Household Support Fund monitoring data published by DWP (HSF4) to understand who received support, how councils delivered it, and how much was spent on food, energy, housing, essentials, administration, and holiday Free School Meal support.

Insights from frontline organisations

Our third source of information was Trussell’s Hunger in the UK study, along with insights from their work with community organisations and members of the Crisis Support Working Group. This evidence highlights people’s lived experiences of crisis, the barriers they face when trying to access support, and the importance of advice and warm referral pathways. It provides essential context that helps explain the patterns in the data and illustrates what effective crisis support looks like in practice.